# Building a Flow NFT pet store

This tutorial will teach you to create a simple NFT marketplace on the Flow (opens new window) blockchain from scratch, using the Flow blockchain and IPFS/Filecoin storage via nft.storage (opens new window). Although we will be building a pet store using pet images, you are free to use your own images and change the metadata.

# Prerequisites

Although this tutorial is built for Flow, it focuses on building up a basic understanding of smart contract and NFTs. You are expected to bring a working JavaScript and basic React.js (opens new window) skills to the table, but a passing familiarity with blockchains, web3, and NFTs will be just fine if you are happy to catch up.

You will need to install Node.js (opens new window) and npm (comes with Node.js), Flow command line tool (opens new window), and Docker compose (opens new window) to follow this tutorial. You're free to use any code editor, but VSCode (opens new window) with Cadence Language support (opens new window) is a great option.

💡 Using React

React.js is the most widely-used UI library that arguably takes away the tediousness of setting up a JavaScript app. You are welcome to work with another library/framework if you are happy to take on the additional work of taking the road less travelled (opens new window) approach.

If you are very new to the concept of smart contracts and NFTs, it is worth checking out blockchain and NFT basics before diving in.

# What you will learn

As we build a minimal version of the Flowwow NFT pet store (opens new window) together, you will learn the basic NFT building blocks from the ground up, including:

- Smart contracts and the Cadence language (opens new window)

- User authentication

- Minting tokens and storing metadata on Filecoin/IPFS via NFT.storage (opens new window)

- Transferring tokens

# Understanding ownership and resource

A blockchain is a digital distributed ledger that tracks an ownership of some resource. There is nothing new about the ledger part—Your bank account is a ledger that keeps track of how much money you own and how much is spent (change of ownership) at any time. The key components to a ledger are:

- Resource at play. In this case a currency.

- Accounts to own the resource, or the access to it.

- Contract or a ruleset to govern the economy.

# Resource

A resource can be any thing — from currency, crop, to digital monster — as long as the type of resource is agreed upon commonly by all accounts.

# Accounts

Each account owns a ledger of its own to keep track of the spending (transferring) and imbursing (receiving) of the resource.

# Contract

A contract is a ruleset governing how the "game" is played. Accounts that break the ruleset may be punished in some way. Normally, it is a central authority like a bank who creates this contract for all accounts.

Because the conventional ledgers are owned and managed by a trusted authority like your bank, when you transfer the ownership of a few dollars (-$4.00) to buy a cup of coffee from Mr. Peet, the bank needs to be consistent and update the ledgers on both sides to reflect the ownership change (Peet has +$4.00 and you have -$4.00). Because both ledgers are not openly visible to both of Peet and you and the the currency is likely digital, there is no guarantee that the bank won't mistakenly or intentionally update either ledger with the incorrect value.

💡 Do you know your bank owes you?

If you have a saving account with some money in it, you might be loaning your money to your bank. You are trusting your bank to have your money when you want to withdraw. Meanwhile, your money is just part of the stream of your bank is free to do anything with. If you had a billion dollars in your bank and you want to withdraw tomorrow, your teller might freak out.

What is interesting about a blockchain is the distributed part. Because there is only a single decentralized ledger that's open to everyone, there is no central authority like a bank for you to trust with bookkeeping. In fact, there is no need for you to trust anyone at all. You only need to trust the copy of the common ledger software run by other people in the network to uphold the bookkeeping, and it is very hard for someone to run an altered version of that software and attempt to break the rule.

A good analogy is an umpire-less tennis game where any dispute (like determining if the ball lands in the court) is distributed to all the audience to judge. Meanwhile, these audience members are also participating in the game, with the stake that makes them lose if they judge wrongly. This way, any small inconsistencies are likely caught and rejected fair and square. You are no longer trusting your bank. The eternal flow of ownerships hence becomes trustless because everyone is doing what's best for themselves.

"Why such emphasis on ownership?" you may ask. This is because Flow has the concept of resource ownership baked right into the smart contract core. Learning to visualize resource will help in understanding concepts in Flow, as you shall see very soon.

# Quick tour of Cadence

Like Solidity language for Ethereum, Flow uses Cadence (opens new window) language to code smart contracts, transactions, and scripts on Flow. Cadence's design is inspired by the Rust (opens new window) and Move (opens new window) languages. In Cadence, the runtime tracks when a resource is being moved from a variable to the next and makes sure it can never be mutually accessible in the program.

The three types of Cadence program you will be writing are contracts (opens new window), transactions (opens new window), and scripts (opens new window).

# Contract

A contract is an initial program that gets deployed to the blockchain, initiating the logic for your app and allowing access to resources you create and the capabilities that come with them.

Two of the most common constructs in a contract are resources and interfaces.

# Resources

Resources are items stored in user accounts that are accessible

through access control measures defined in the contract. They are usually the assets being tracked or some capabilities, such as a capability to withdraw an asset from an account. They are akin to classes or structs in some languages. Resources can only be in one place at a time, and they are said to be moved rather than assigned.

# Interfaces

Interfaces define the behaviors or capabilities of resources. They are akin to interfaces in some languages. They are usually implemented by other resources. Interfaces are also defined with the keyword resource.

Here is an example of an NFT resource and an Ownable interface (à la ERC721 (opens new window)) in a separate PetShop contract:

pub contract PetShop {

// A map recording owners of NFTs

pub var owners: {UInt64 : Address}

// A Transferrable interface declaring some methods or "capabilities"

pub resource interface Transferrable {

pub fun owner(): Address

pub fun transferTo(recipient: Address)

}

// NFT resource implements Transferrable

pub resource NFT: Transferrable {

// Unique id for each NFT.

pub let id: UInt64

// Constructor method

init(initId: UInt64) {

self.id = initId

}

pub fun owner(): Address {

return owners[self.id]!

}

pub fun transferTo(recipient: Address) {

// Code to transfer this NFT resource to the recipient's address.

}

}

}

Note the access modifier pub before each definition. This declares public access for all user accounts. Writing a Cadence contract revolves around designing access control.

# Transaction

Transactions tell the on-chain contract to change the state of the chain. Like Ethereum, the change is synchronized throughout the peers and cannot be undone. Therefore, a transaction is considered a write operation that incurs a network gas fee. Transactions require one or more accounts to sign and authorize. For instance, minting and transferring tokens are transactions.

Here is an example of a transaction which requires a current account to sign a certain action that mutate the chain's state. In this case, just logging "Hello, transaction".

transaction(tokenId: UInt64, recipientAddr: Address) {

// The field holds the NFT as it is being transferred.

let token: @PetStore.NFT

// Takes the sending account as a parameter to

prepare(acc: AuthAccount) {

// This is the code that requires a signature, such as

// withdrawing a token from the signing account.

}

execute {

// This is the code that does not require a signature.

log("Hello, transaction")

}

}

# Script

Scripts are Cadence programs that are run on the client to read the state of the chain. Therefore, they do not incur any gas fee and do not need an account to sign them.

Here is an example of a script reading an NFT's current owner's account address by accessing the map field named owners on the contract by an NFT id:

// Take a target NFT's id as a parameter and return an Address

// of the current owner of that NFT.

pub fun main(id: UInt64) : Address {

return PetStore.owner[id]!

}

Both transactions and scripts are invoked on the client side.

💡 Interface in other languages

If you have programmed in a typed language like Java, Rust, or TypeScript, you might be familiar with the interface, which is a description of capabilities versus a concrete entity like a class or struct. In Cadence, a resource is similar to a class or struct and an interface is the same as those in Java or Rust.

# Building pet store

Now that we had a quick tour of Cadence, we are ready to start building the mini NFT pet store! We will be learning as we build.

Create a new React app by typing the following commands in your shell:

npx create-react-app petstore; cd petstore

And initialize a Flow project:

flow init

You should see a new React project created with a flow.json configuration file inside. Let's take a closer look at the structure and configure the project.

# Project structure

First of all, note the flow.json file under the root directory. This configuration file was created when we typed the command flow init and tells Flow that this is a Flow project. We will leave most of the initial settings as they were, but make sure it contains these fields by adding or changing them accordingly:

{

// ...

"contracts": {

"PetStore": "./src/flow/contracts/PetStore.cdc"

},

"deployments": {

"emulator": {

"emulator-account": ["PetStore"]

}

},

// ...

}

These fields tell Flow where to look for the contract so we will be able to run the command line to deploy it to the Flow emulator. Now we will need to add some directories for our Cadence code.

Because create-react-app forbids importing code from outside of the src directory, the majority of the code we write will be under src.

Create a directory named flow inside src directory, and create three more subdirectories named contract, transaction, and script under flow. This can be combined into one command:

mkdir -p src/flow/{contract,transaction,script}

As you might have guessed, each directory will contain the corresponding Cadence code for each type of interaction.

Now, in each of these directories, create a Cadence file with the following names: contract/PetStore.cdc, transaction/MintToken.cdc, and script/GetTokenIds.cdc.

The structure of the src directory should now look like this:

.

|— flow

| |— contract

| | |

| | `— PetStore.cdc

| |— script

| | |

| | `— GetTokenIds.cdc

| `— transaction

| |

| `— MintToken.cdc

|

...

# PetStore contract

💡 Don't reinvent the wheel

As you move toward building on testnet and finally mainnet, you will want to take a look at existing interfaces (opens new window) and implement them. However, building our own interfaces is a great way to learn, and learning is our goal here.

Now, we will write our first contract.

First, create the contract structure and define an NFT resource:

pub contract PetStore {

// An array that stores NFT owners

pub var owners: {UInt64: Address}

pub resource NFT {

// Unique ID for each NFT

pub let id: UInt64

// String mapping to hold metadata

pub var metadata: {String: String}

// Constructor method

init(id: UInt64, metadata: {String: String}) {

self.id = id

self.metadata = metadata

}

}

}

Note that we have declared a Dictionary (opens new window) and stored it in a variable named owners. This dictionary has the type {UInt64: Address} which maps unsigned 64-bit integers (opens new window) to users' Addresses (opens new window). We will use owners to keep track of all the current owners of NFTs globally.

Also note that the owners variable is prepended by a var keyword, while the id variable is prepended by a let keyword. In Cadence, a mutable variable is defined using var while an immutable one is defined with let.

💡 Immutable vs mutable

In Cadence, a variable stores a mutable variable that can be changed later in the program while a binding binds an immutable value that cannot be changed.

In the body of NFT resource, we declare id field and a constructor method to assign the id to the NFT instance.

# NFTReceiver

Next, we create an NFTReceiver interface that defines the capabilities or methods of a receiver of NFTs, or the rest of the users who are not the contract user.

To reiterate, an interface is not an instance of an object, like a user account. It is a set of behaviors, or capabilities in Cadence's speak, that a resource can implement to become capable of certain actions, like withdrawing and depositing tokens.

pub contract PetStore {

// ... The @NFT code ...

pub resource interface NFTReceiver {

// Withdraw a token by its ID and returns the token.

pub fun withdraw(id: UInt64): @NFT

// Deposit an NFT to this NFTReceiver instance.

pub fun deposit(token: @NFT)

// Get all NFT IDs belonging to this NFTReceiver instance.

pub fun getTokenIds(): [UInt64]

// Get the metadata of an NFT instance by its ID.

pub fun getTokenMetadata(id: UInt64) : {String: String}

// Update the metadata of an NFT.

pub fun updateTokenMetadata(id: UInt64, metadata: {String: String})

}

}

Let's not get over ourselves and go through the NFTReceiver interface line-by-line.

The withdraw(id: UInt64): @NFT method takes an NFT's id, withdraws a token, or an instance of NFT resource, which is prepended with a @ to indicate a reference to a resource.

The deposit(token: @NFT) method takes a token reference type @NFT and deposits or transfers it to the current instance of NFTReceiver.

The getTokenIds(): [UInt64] method accesses all tokens IDs owned by the instance of the NFTReceiver.

The getTokenMetadata(id: UInt64) : {String : String} method takes an ID of an NFT, reads the metadata, and returns it as a dictionary.

The updateTokenMetadata(id: UInt64, metadata: {String: String}) method takes an ID of an NFT and a metadata dictionary to update the target NFT's metadata.

# NFTCollection

Now let's create an NFTCollection resource to implement the NFTReceiver interface. Think of this as a "vault" where NFTs can be deposited or withdrawn.

pub contract PetStore {

// ... The @NFT code ...

// ... The @NFTReceiver code ...

pub resource NFTCollection: NFTReceiver {

// Keeps track of NFTs this collection.

access(account) var ownedNFTs: @{UInt64: NFT}

// Constructor

init() {

self.ownedNFTs <- {}

}

// Destructor

destroy() {

destroy self.ownedNFTs

}

// Withdraws and return an NFT token.

pub fun withdraw(id: UInt64): @NFT {

let token <- self.ownedNFTs.remove(key: id)

return <- token!

}

// Deposits a token to this NFTCollection instance.

pub fun deposit(token: @NFT) {

self.ownedNFTs[token.id] <-! token

}

// Returns an array of the IDs that are in this collection.

pub fun getTokenIds(): [UInt64] {

return self.ownedNFTs.keys

}

// Returns the metadata of an NFT based on the ID.

pub fun getTokenMetadata(id: UInt64): {String : String} {

let metadata = self.ownedNFTs[id]?.metadata

return metadata!

}

// Updates the metadata of an NFT based on the ID.

pub fun updateTokenMetadata(id: UInt64, metadata: {String: String}) {

for key in metadata.keys {

self.ownedNFTs[id]?.metadata?.insert(key: key, metadata[key]!)

}

}

}

// Public factory method to create a collection

// so it is callable from the contract scope.

pub fun createNFTCollection(): @NFTCollection {

return <- create NFTCollection()

}

}

That's a handful of new code. It will soon become natural to you with patience.

First we declare a mutable dictionary and store it in a variable named ownedNFTs. Note the new access modifier pub(set), which gives public write access to the users.

This dictionary stores the NFTs for this collection by mapping the ID to NFT resource. Note that because the dictionary stores @NFT resources, we prepend the type with @, making itself a resource too.

In the contructor method, init(), we instantiate the ownedNFTs with an empty dictionary. A resource also needs a destroy() destructor method to make sure it is being freed.

💡 Nested Resource

A composite structure (opens new window) including a dictionary can store resources, but when they do they will be treated as resources. Which means they need to be moved rather than assigned and their type will be annotated with@.

The withdraw(id: UInt64): @NFT method removes an NFT from the collection's ownedNFTs array and return it.

The left-pointing arrow <- is known as a move symbol, and we use it to move a resource around. Once a resource has been moved, it can no longer be used from the old variable.

Note the ! symbol after the token variable. It force-unwraps (opens new window) the Optional value. If the value turns out to be nil, the program panics and crashes.

Because resources are core to Cadence, their types are annotated with a @ to make them explicit. For instance, @NFT and @NFTCollection are two resource types.

The deposit(token: @NFT) function takes the @NFT resource as a parameter and stores it in the ownedNFTs array in this @NFTCollection instance.

The ! symbol reappears here, but now it's after the move arrow <-!. This is called a force-move or force-assign (opens new window) operator, which only moves a resource to a variable if the variable is nil. Otherwise, the program panics.

The getTokenIds(): [UInt64] method simply reads all the UInt64 keys of the ownedNFTs dictionary and returns them as an array.

The getTokenMetadata(id: UInt64): {String : String} method reads the metadata field of an @NFT stored by its ID in the ownedNFTs dictionary and returns it.

The updateTokenMetadata(id: UInt64, metadata: {String: String}) method is a bit more involved.

for key in metadata.keys {

self.ownedNFTs[id]?.metadata?.insert(key: key, metadata[key]!)

}

In the body of the method, we loop over all the keys of the given metadata, inserting into the current metadata dictionary the new value. Note the ? in the call chain. It is used with Optionals values to keep going down the call chain only if the value is not nil.

We have successfully implemented the @NFTReceiver interface for the @NFTCollection resource.

# NFTMinter

The last and very important component for our PetStore contract is @NFTMinter resource, which will contain an exclusive code for the contract owner to mint all the tokens. Without it, our store will not be able to mint any pet tokens. It is very simplistic though, since we have already blazed through the more complex components. Its only mint(): @NFT method creates an @NFT resource, gives it an ID, saves the address of the first owner to the contract (which is the address of the contract owner, although you could change it to mint and transfer to the creator's address in one step), increments the universal ID counter, and returns the new token.

pub contract PetStore {

// ... NFT code ...

// ... NFTReceiver code ...

// ... NFTCollection code ...

pub resource NFTMinter {

// Declare a global variable to count ID.

pub var idCount: UInt64

init() {

// Instantialize the ID counter.

self.idCount = 1

}

pub fun mint(_ metadata: {String: String}): @NFT {

// Create a new @NFT resource with the current ID.

let token <- create NFT(id: self.idCount, metadata: metadata)

// Save the current owner's address to the dictionary.

PetStore.owners[self.idCount] = PetStore.account.address

// Increment the ID

self.idCount = self.idCount + 1 as UInt64

return <-token

}

}

}

By now, we have all the nuts and bolts we need for the contract. The only thing that is missing is a way to initialize this contract at deployment time. Let's create a constructor method to create an empty @NFTCollection instance for the deployer of the contract (you) so it is possible for the contract owner to mint and store NFTs from the contract. As we go over this last hurdle, we will also learn about the other important concept in Cadence—Storage and domains (opens new window).

pub contract PetStore {

// ... @NFT code ...

// ... @NFTReceiver code ...

// ... @NFTCollection code ...

// This contract constructor is called once when the contract is deployed.

// It does the following:

//

// - Creating an empty Collection for the deployer of the collection so

// the owner of the contract can mint and own NFTs from that contract.

//

// - The `Collection` resource is published in a public location with reference

// to the `NFTReceiver` interface. This is how we tell the contract that the functions defined

// on the `NFTReceiver` can be called by anyone.

//

// - The `NFTMinter` resource is saved in the account storage for the creator of

// the contract. Only the creator can mint tokens.

init() {

// Set `owners` to an empty dictionary.

self.owners = {}

// Create a new `@NFTCollection` instance and save it in `/storage/NFTCollection` domain,

// which is only accessible by the contract owner's account.

self.account.save(<-create NFTCollection(), to: /storage/NFTCollection)

// "Link" only the `@NFTReceiver` interface from the `@NFTCollection` stored at `/storage/NFTCollection` domain to the `/public/NFTReceiver` domain, which is accessible to any user.

self.account.link<&{NFTReceiver}>(/public/NFTReceiver, target: /storage/NFTCollection)

// Create a new `@NFTMinter` instance and save it in `/storage/NFTMinter` domain, accesible

// only by the contract owner's account.

self.account.save(<-create NFTMinter(), to: /storage/NFTMinter)

}

}

Hopefully, the high-level steps are clear to you after you have followed through the comments. We will talk about domains briefly here. Domains are general-purpose storages accessible to Flow accounts commonly used for storing resources. Intuitively, they are similar to common filesystems. There are three domain namespaces in Cadence:

# /storage

This namespace can only be accessed by the owner of the account.

# /private

This namespace is used to stored private objects and capabilities (opens new window) whose access can be granted to selected accounts.

# /public

This namespace is accessible by all accounts that interact with the contract.

In our previous code, we created an @NFTCollection instance for our own account and saved it to the /storage/NFTCollection namespace. The path following the first namespace is arbitrary, so we could have named it /storage/my/nft/collection. Then, something odd happened as we "link" a reference (opens new window) to the @NFTReceiver capability from the /storage domain to /public. The caret pair < and > was used to explicitly annotate the type of the reference being linked, &{NFTReceiver}, with the & and the wrapping brackets { and } to define the unauthorized reference type (see References (opens new window) to learn more). Last but not least, we created the @NFTMinter instance and saved it to our account's /storage/NFTMinter domain.

For a deep dive into storages, check out Account Storage (opens new window).

As we wrap up our PetStore contract, let's try to deploy it to the Flow emulator to verify the contract. Start the emulator by typing flow emulator in your shell.

flow emulator

> INFO[0000] ⚙️ Using service account 0xf8d6e0586b0a20c7 serviceAddress=f8d6e0586b0a20c7 serviceHashAlgo=SHA3_256 servicePrivKey=bd7a891abd496c9cf933214d2eab26b2a41d614d81fc62763d2c3f65d33326b0 servicePubKey=5f5f1442afcf0c817a3b4e1ecd10c73d151aae6b6af74c0e03385fb840079c2655f4a9e200894fd40d51a27c2507a8f05695f3fba240319a8a2add1c598b5635 serviceSigAlgo=ECDSA_P256

> INFO[0000] 📜 Flow contracts FlowFees=0xe5a8b7f23e8b548f FlowServiceAccount=0xf8d6e0586b0a20c7 FlowStorageFees=0xf8d6e0586b0a20c7 FlowToken=0x0ae53cb6e3f42a79 FungibleToken=0xee82856bf20e2aa6

> INFO[0000] 🌱 Starting gRPC server on port 3569 port=3569

> INFO[0000] 🌱 Starting HTTP server on port 8080 port=8080

Take note of the FlowServiceAccount address, which is a hexadecimal number 0xf8d6e0586b0a20c7 (In fact, these numbers are so ubiquitous in Flow that it has its own Address (opens new window) type). This is the address of the contract on the emulator.

Open up a new shell, making sure you are inside the project directory, then type flow project deploy to deploy our first contract. You should see an output similar to this if it was successful:

flow project deploy

> Deploying 1 contracts for accounts: emulator-account

>

> PetStore -> 0xf8d6e0586b0a20c7 (11e3afe90dc3a819ec9736a0a36d29d07a2f7bca856ae307dcccf4b455788710)

>

>

> ✨ All contracts deployed successfully

Congratulations! You have learned how to write and deploy your first smart contract.

⚠️ Oops! That didn't work

Checkflow.jsonconfiguration and make sure the path to the contract is correct.

# MintToken transaction

The first and most important transaction for any NFT app is perhaps the one that mints tokens into existence! Without it there won't be any cute tokens to sell and trade. So let's start coding:

// MintToken.cdc

// Import the `PetStore` contract instance from the master account address.

// This is a fixed address for used with the emulator only.

import PetStore from 0xf8d6e0586b0a20c7

transaction(metadata: {String: String}) {

// Declare an "unauthorized" reference to `NFTReceiver` interface.

let receiverRef: &{PetStore.NFTReceiver}

// Declare an "authorized" reference to the `NFTMinter` interface.

let minterRef: &PetStore.NFTMinter

// `prepare` block always take one or more `AuthAccount` parameter(s) to indicate

// who are signing the transaction.

// It takes the account info of the user trying to execute the transaction and

// validate. In this case, the contract owner's account.

// Here we try to "borrow" the capabilities available on `NFTMinter` and `NFTReceiver`

// resources, and will fail if the user executing this transaction does not have access

// to these resources.

prepare(account: AuthAccount) {

// Note that we have to call `getCapability(_ domain: Domain)` on the account

// object before we can `borrow()`.

self.receiverRef = account.getCapability<&{PetStore.NFTReceiver}>(/public/NFTReceiver)

.borrow()

?? panic("Could not borrow receiver reference")

// With an authorized reference, we can just `borrow()` it.

// Note that `NFTMinter` is borrowed from `/storage` domain namespace, which

// means it is only accessible to this account.

self.minterRef = account.borrow<&PetStore.NFTMinter>(from: /storage/NFTMinter)

?? panic("Could not borrow minter reference")

}

// `execute` block executes after the `prepare` block is signed and validated.

execute {

// Mint the token by calling `mint(metadata: {String: String})` on `@NFTMinter` resource, which returns an `@NFT` resource, and move it to a variable `newToken`.

let newToken <- self.minterRef.mint(metadata)

// Call `deposit(token: @NFT)` on the `@NFTReceiver` resource to deposit the token.

// Note that this is where the metadata can be changed before transferring.

self.receiverRef.deposit(token: <-newToken)

}

}

⚠️ Ambiguous type warning

If you are using VSCode, chances are you might see the editor flagging the

lines referring toPetStore.NFTReceiverandPetStore.NFTMintertypes

with an "ambiguous type <T> not found". Try to reset the running emulator

by pressingCtrl+Cin the shell where you ran the emulator to interrupt it

and run it again withflow emulatorand on a different shell, don't forget

to redeploy the contract withflow project deploy.

The first line of the transaction code imports the PetStore contract instance.

The transaction block takes an arbitrary number of named parameters, which will be provided by the calling program (In Flow CLI, JavaScript, Go, or other language). These parameters are the only channels for the transaction code to interact with the outside world.

Next, we declare references &{NFTReceiver} and &NFTMinter (Note the first is an unauthorized reference).

Now we enter the prepare block, which is responsible for authorizing the transaction. This block takes an argument of type AuthAccount. This account instance is required to sign and validate the transaction with its key. If it takes more than one AuthAccount parameters, then the transaction becomes a multi-signature transaction. This is the only place our code can access the account object.

What we did was calling getCapability(/public/NFTReceiver) on the account instance, then borrow() to borrow the reference to NFTReceiver and gain the capability for receiverRef to receive tokens. We also called borrow(from: /storage/NFTMinter) on the account to enable minterRef with the superpower to mint tokens into existence.

The execute block runs the code within after the prepare block succeeds. Here, we called mint(metadata: {String: String}) on the minterRef reference, then moved the newly created @NFT instance into a newToken variable. After, we called deposit(token: @NFT) on the receiverRef reference, passing <-newToken (@NFT resource) as an argument. The newly minted token is now stored in our account's receiverRef.

Let's try to send this transaction to the running emulator and mint a token! Because this transaction takes a metadata of type {String: String} (string to string dictionary), we will need to pass that argument when sending the command via Flow CLI.

With a bit of luck, you should get a happy output telling you that the transaction is sealed.

flow transactions send src/flow/transaction/MintToken.cdc '{"name": "Max", "breed": "Bulldog"}'

> Transaction ID: b10a6f2a1f1d88f99e562e72b2eb4fa3ae690df591d5a9111318b07b8a72e060

>

> Status ✅ SEALED

> ID b10a6f2a1f1d88f99e562e72b2eb4fa3ae690df591d5a9111318b07b8a72e060

> Payer f8d6e0586b0a20c7

> Authorizers [f8d6e0586b0a20c7]

> ...

Note the transaction ID returned from the transaction. Every transaction returns an ID no matter if it succeeds or not.

Congratulations on minting your first NFT pet! It does not have a face yet besides just a name and a breed. But later in this tutorial, we will upload static images for our pets onto the Filecoin/IPFS networks using nft.storage (opens new window).

# TransferToken transaction

Now that we know how to mint Flow NFTs, the next natural step is to learn how to transfer them to different users. Since this transfer action writes to the blockchain and mutates the state, it is also a transaction.

Before we can transfer a token to another user's account, we need another receiving account to deposit a token to. (We could transfer a token to our address, but that wouldn't be very interesting, would it?) At the moment, we have been working with only our emulator account so far. So, let's create an account through the Flow CLI.

First, create a public-private key pair by typing flow keys generate. The output should look similar to the following, while the keys will be different:

flow keys generate

> 🔴️ Store private key safely and don't share with anyone!

> Private Key f410328ecea1757efd2e30b6bc692277a51537f30d8555106a3186b3686a2de6

> Public Key be393a6e522ae951ed924a88a70ae4cfa4fd59a7411168ebb8330ae47cf02aec489a7e90f6c694c4adf4c95d192fa00143ea8639ea795e306a27e7398cd57bd9

For convenience, let's create a JSON file named .keys.json in the root directory next to flow.json so we can read them later on:

{

"private": "f410328ecea1757efd2e30b6bc692277a51537f30d8555106a3186b3686a2de6",

"public": "be393a6e522ae951ed924a88a70ae4cfa4fd59a7411168ebb8330ae47cf02aec489a7e90f6c694c4adf4c95d192fa00143ea8639ea795e306a27e7398cd57bd9"

}

Next, type this command, replacing <PUBLIC_KEY> with the public key you generated to create a new account:

flow accounts create —key <PUBLIC_KEY> —signer emulator-account

> Transaction ID: b19f64d3d6e05fdea5dd2ac75832d16dc61008eeacb9d290f153a7a28187d016

>

> Address 0xf3fcd2c1a78f5eee

> Balance 0.00100000

> Keys 1

>

> ...

Take note of the new address, which should be different from the one shown here. Also, you might notice there is a transaction ID returned. Creating an account is also a transaction, and it was signed by the emulator-account (hence, —signer emulator-account flag).

Before we can use the new address, we need to tell the Flow project about it. Open the flow.json configuration file, and at the "accounts" field, add the new account name ("test-account" here, but it could be any name), address, and the private key:

{

// ...

"accounts": {

"emulator-account": {

"address": "f8d6e0586b0a20c7",

"key": "bd7a891abd496c9cf933214d2eab26b2a41d614d81fc62763d2c3f65d33326b0"

},

"test-account": {

"address": "0xf3fcd2c1a78f5eee",

"key": <PRIVATE_KEY>

}

}

// ...

}

With this new account created, we are ready to move on to the next step.

Before we can deposit a token to the new account, we need it to "initialize" its collection. We can do this by creating a transaction for every user to initialize an NFTCollection in order to receive NFTs.

Inside /transactions directory next to MintToken.cdc, create a new Cadence file named InitCollection.cdc:

// InitCollection.cdc

import PetStore from 0xf8d6e0586b0a20c7

// This transaction will be signed by any user account who wants to receive tokens.

transaction {

prepare(acct: AuthAccount) {

// Create a new empty collection for this account

let collection <- PetStore.NFTCollection.new()

// store the empty collection in this account storage.

acct.save<@PetStore.NFTCollection>(<-collection, to: /storage/NFTCollection)

// Link a public capability for the collection.

// This is so that the sending account can deposit the token to this account's

// collection by calling its `deposit(token: @NFT)` method.

acct.link<&{PetStore.NFTReceiver}>(/public/NFTReceiver, target: /storage/NFTCollection)

}

}

This small code will be signed by a receiving account to create an NFTCollection instance and save it to their own private /storage/NFTCollection domain (Recall that anything stored in /storage domain can only be accessible by the current account). In the last step, we linked the NFTCollection we have just stored to the public domain /public/NFTReceiver (and in the process, "casting" the collection up to NFTReceiver) so whoever is sending the token can access this and call deposit(token: @NFT) on it to deposit the token.

Try sending this transaction by typing the command:

flow transactions send src/flow/transaction/InitCollection.cdc —signer test-account

Note that test-account is the name of the new account we created in the flow.json file. Hopefully, the new account should now have an NFTCollection created and ready to receive tokens!

Now, create a Cadence file named TransferToken.cdc in the /transactions directory with the following code.

// TransferToken.cdc

import PetStore from 0xf8d6e0586b0a20c7

// This transaction transfers a token from one user's

// collection to another user's collection.

transaction(tokenId: UInt64, recipientAddr: Address) {

// The field holds the NFT as it is being transferred to the other account.

let token: @PetStore.NFT

prepare(account: AuthAccount) {

// Create a reference to a borrowed `NFTCollection` capability.

// Note that because `NFTCollection` is publicly defined in the contract, any account can access it.

let collectionRef = account.borrow<&PetStore.NFTCollection>(from: /storage/NFTCollection)

?? panic("Could not borrow a reference to the owner's collection")

// Call the withdraw function on the sender's Collection to move the NFT out of the collection

self.token <- collectionRef.withdraw(id: tokenId)

}

execute {

// Get the recipient's public account object

let recipient = getAccount(recipientAddr)

// This is familiar since we have done this before in the last `MintToken` transaction block.

let receiverRef = recipient.getCapability<&{PetStore.NFTReceiver}>(/public/NFTReceiver)

.borrow()

?? panic("Could not borrow receiver reference")

// Deposit the NFT in the receivers collection

receiverRef.deposit(token: <-self.token)

// Save the new owner into the `owners` dictionary for look-ups.

PetStore.owners[tokenId] = recipientAddr

}

}

Recall that in the last steps of our MintToken.cdc code, we were saving the minted token to our account's NFTCollection reference stored at /storage/NFTCollection domain.

Here in TransferToken.cdc, we are basically creating a sequel of the minting process. The overall goal is to move the token stored in the sending source account's NFTCollection to the receiving destination account's NFTCollection by calling withdraw(id: UInt64) and deposit(token: @NFT) on the sending and receiving collections, respectively. Hopefully, by now it shouldn't be too difficult for you to follow along with the comments as you type down each line.

Two new things that are worth noting are the first line of the execute block where we call a special built-in function getAccount(_ addr: Address), which returns an AuthAccount instance from an address passed as an argument to this transaction, and the last line, where we update the owners dictionary on the PetStore contract with the new address entry to keep track of the current NFT owners.

Now, let's test out TransferToken.cdc by typing the command:

flow transactions send src/flow/transaction/TransferToken.cdc 1 0xf3fcd2c1a78f5eee

> Transaction ID: 4750f983f6b39d87a1e78c84723b312c1010216ba18e233270a5dbf1e0fdd4e6

>

> Status ✅ SEALED

> ID 4750f983f6b39d87a1e78c84723b312c1010216ba18e233270a5dbf1e0fdd4e6

> Payer f8d6e0586b0a20c7

> Authorizers [f8d6e0586b0a20c7]

>

> ...

Recall that the transaction block of TransferToken.cdc accepts two arguments — A token ID and the recipient's address — which we passed as a list of arguments to the command. Some of you might wonder why we left out --signer flag for this transaction command, but not the other. Without passing the signing account's name to --signer flag, the contract owner's account is the signer by default (a.k.a the AuthAccount argument in the prepare block).

Well done! You have just withdrawn and deposited your NFT to another account!

# GetTokenOwner script

We have learned to write and send transactions. Now, we will learn how to create scripts to read state from the blockchain.

There are many things we can query using a script, but since we have just transferred a token to test-account, it would be nice to confirm that the token was actually transferred.

Let's create a script file named GetTokenOwner.cdc under the script directory:

// GetTokenOwner.cdc

import PetStore from 0xf8d6e0586b0a20c7

// All scripts start with the `main` function,

// which can take an arbitrary number of argument and return

// any type of data.

//

// This function accepts a token ID and returns an Address.

pub fun main(id: UInt64): Address {

// Access the address that owns the NFT with the provided ID.

let ownerAddress = PetStore.owners[id]!

return ownerAddress

}

All scripts have an entry function called main, which can take any number of arguments and return any data type.

In this script, the main function accesses the owners dictionary in the PetStore contract using the token ID and returns the address of the token's owner, or fails if the value is nil.

As a reminder, scripts do not require any gas fee or authorization because they only read public data on the blockchain rather than writing to it.

Here's how to execute a script with the Flow CLI:

flow scripts execute src/flow/script/GetTokenOwner.cdc <TOKEN_ID>

<TOKEN_ID> is an unsigned integer token ID starting from 1. If you have minted an NFT and transferred it to the test-account, then replace <TOKEN_ID> with the token ID. You should get back the address of the test-account you have created.

# GetTokenMetadata script

From GetTokenOwner.cdc script, it takes only a few more steps to create a script that returns a token's metadata.

We will work on GetTokenMetadata.cdc which, as the name suggests, gets the metadata of an NFT based on the given ID.

Recall that there is a metadata variable in the NFT resource definition in the contract which stores a {String: String} dictionary of that NFT's metadata. Our script will have to query the right NFT and read the variable.

Because we already know how to get an NFT's owner address, all we have to do is to access NFTReceiver capability of the owner's account and call getTokenMetadata(id: UInt64) : {String: String} on it to get back the NFT's metadata.

// GetTokenMetadata.cdc

import PetStore from 0xf8d6e0586b0a20c7

// All scripts start with the `main` function,

// which can take an arbitrary number of argument and return

// any type of data.

//

// This function accepts a token ID and returns a metadata dictionary.

pub fun main(id: UInt64) : {String: String} {

// Access the address that owns the NFT with the provided ID.

let ownerAddress = PetStore.owners[id]!

// We encounter the `getAccount(_ addr: Address)` function again.

// Get the `AuthAccount` instance of the current owner.

let ownerAcct = getAccount(ownerAddress)

// Borrow the `NFTReceiver` capability of the owner.

let receiverRef = ownerAcct.getCapability<&{PetStore.NFTReceiver}>(/public/NFTReceiver)

.borrow()

?? panic("Could not borrow receiver reference")

// Happily delegate this query to the owning collection

// to do the grunt work of getting its token's metadata.

return receiverRef.getTokenMetadata(id: id)

}

Now, execute the script:

flow scripts execute src/flow/script/GetTokenMetadata.cdc <TOKEN_ID>

If we have minted an NFT with the metadata {"name": "Max", "breed": "Bulldog"} in the previous minting step, then that is what you will get after running the script.

# GetAllTokenIds (Bonus)

This script is very short and straightforward, and it will become handy

when we build a UI to query tokens based on their IDs.

// GetAllTokenIds.cdc

import PetStore from 0xPetStore

pub fun main() : [UInt64] {

// We basically just return all the UInt64 keys of `owners`

// dictionary as an array to get all IDs of all tokens in existence.

return PetStore.owners.keys

}

Et voila! You have come very far and dare I say you are ready to start building your own Flow NFT app.

However, user experience is a crucial part in any app. It is more than likely that your users won't be as proficient at the command line as you are. Moreover, it is a bit boring for an NFT store to have faceless NFTs. In the next section, we will start tackling the fun part: building the UI on top and using nft.storage (opens new window) service to upload and store images of our NFTs.

# Front-end app

💡 Do you know React?

In this part of the tutorial, we will work with React.js extensively. Because learning React is unfortunately out of the scope, if you think you will need some introduction or brush-up on React, please head over to Intro to React (opens new window) tutorial before returning here.

Our NFT pet store is fully functional at the command line, but without a face, it is too hard for end users to use.

Very often, especially for decentralized applications (opens new window) whose back-ends rely heavily on blockchains and other decentralized technology, the user experience is what makes or breaks them. Quite often, the user-facing part is the only crucial part in a dapp.

In this section, we will be working on the UI for the pet store app in React.js. While you're expected to have some familiarity with the library, I will do my best to use common features instead of trotting into advanced ones.

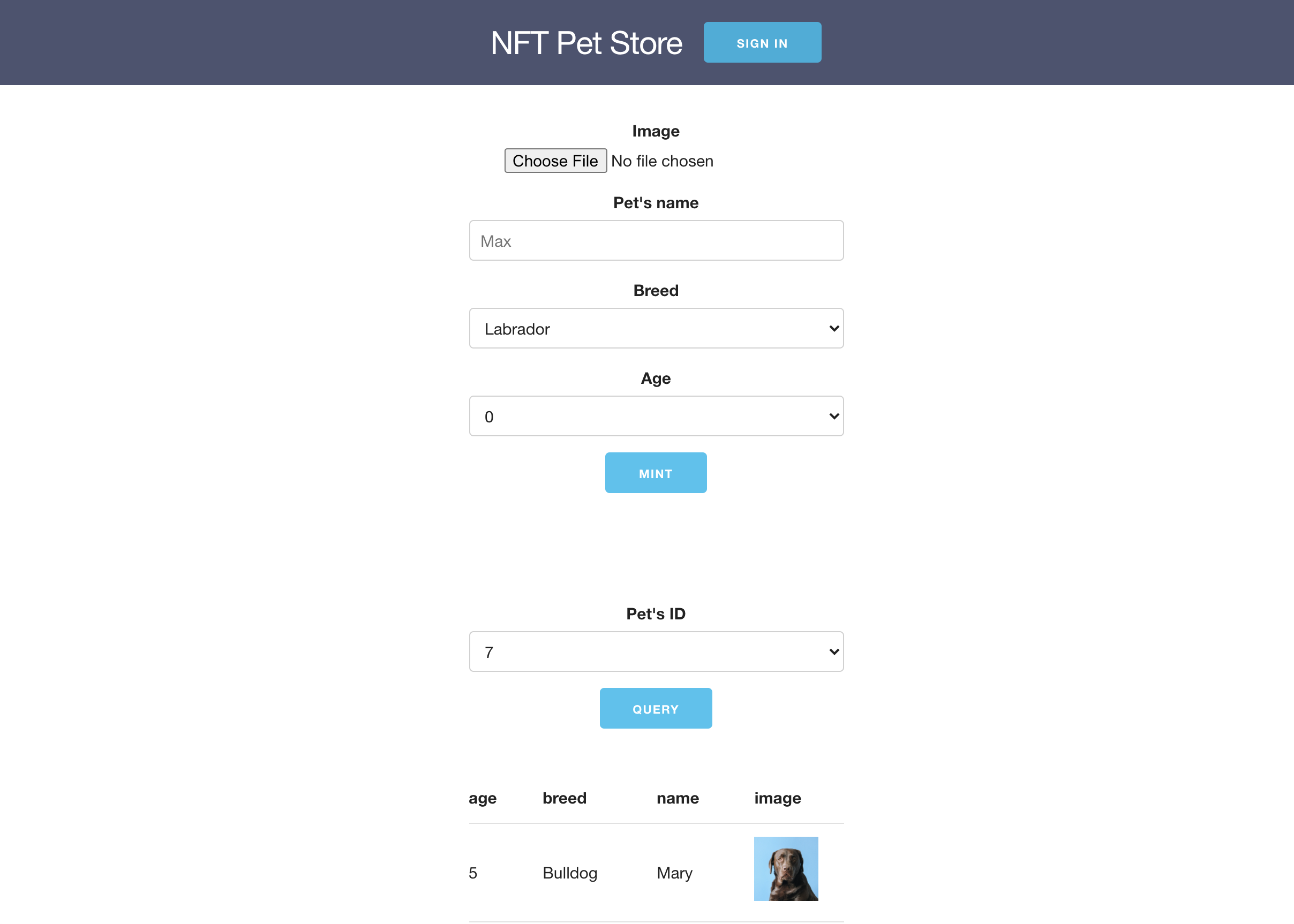

After we are done, we will end up with a simple marketplace app that users can mint and query their NFTs. It will be similar to this:

# Setting up

Make sure you are in the project directory (next to package.json). Install the following packages:

npm install —save @onflow/fcl @onflow/types nft.storage

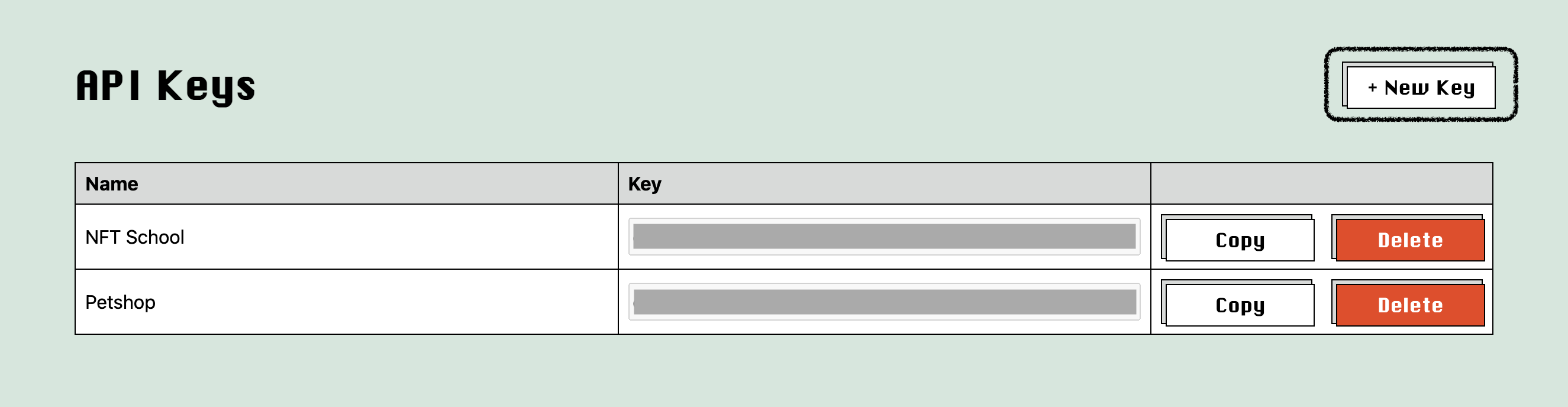

The Flow packages will help in connecting our React app to the Cadence code. The nft.storage package will help in uploading the image during minting and retrieving data from Filecoin/IPFS network. In order to do so, you will need to sign up (opens new window) and generate an API key. After you have signed up, navigate to the "API Keys" tab, and click to create a new key, as shown here:

Copy and save the key as we will need it later on when we work on the minting logic.

Also, to get styling out of the way, please download Skeleton CSS (opens new window) and unzip all the CSS files into the src directory. Then, in the App.css stylesheet, after the last line, import all the stylesheets you just unzipped with:

/* App.css */

@import "./skeleton.css";

@import "./normalize.css";

/* import all other CSS files if any */

Because we want to focus on the UI integration, I'll tell you when to just copy the code that isn't important.

Run the app with npm run start, the React app should open in the browser on http://localhost:3000. Keep the browser open to see the updates as you save your progress.

In your editor, open App.js and remove all the current HTML, leaving only the <div className="App"> level.

function App() {

return (

<div className="App">

{/* Remove code here */}

</div>

);

}

After you save the file, the app in the browser should become blank.

Now, create a new directory named components inside src to keep our reusable components.

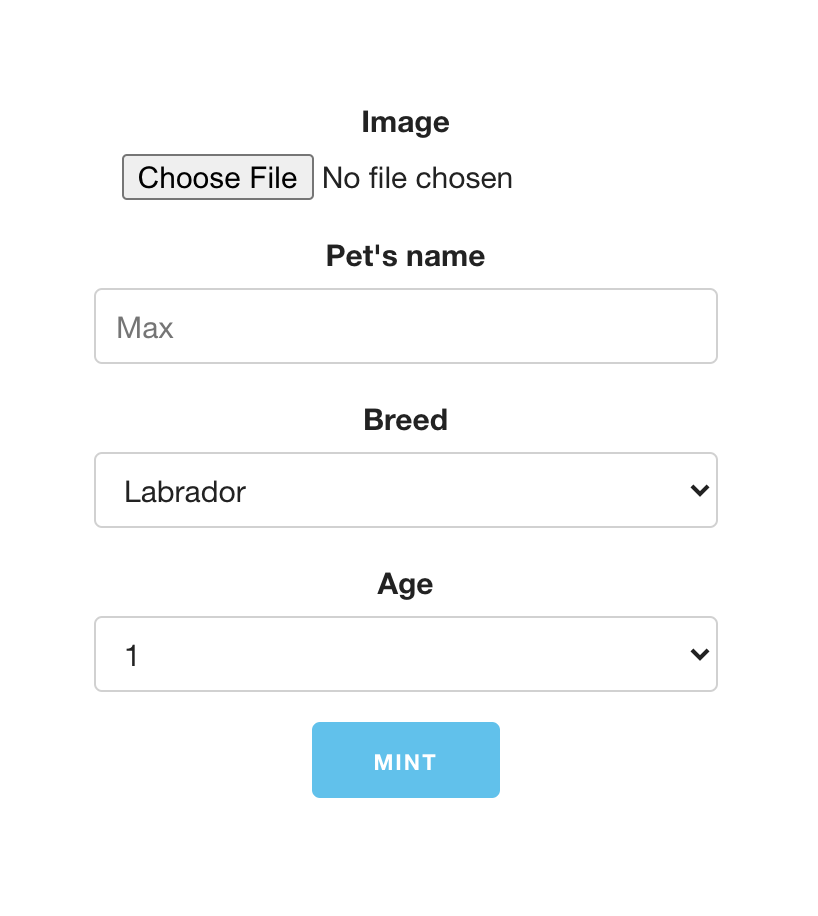

Inside the newly created directory, create a new file named Form.js. This will be a form component that will allow users to submit and mint new NFTs.

// components/Form.js

import FileSelector from './FileSelector';

// Collect the information of a pet and manage as a state

// and mint the NFT based on the information.

const Form = () => {

const [pet, setPet] = useState({});

// Helper functions to be passed to input elements' onChange.

const setName = (event) => {

const name = event.target.value;

setPet({...pet, name});

}

const setBreed = (event) => {

const breed = event.target.value;

setPet({...pet, breed});

}

const setAge = (event) => {

const age = event.target.value;

setPet({...pet, age});

}

return (

<div style={style}>

<form>

<div className="row">

<FileSelector pet={pet} setPet={setPet} />

<div>

<label for="nameInput">Pet's name</label>

<input

className="u-full-width"

type="text"

placeholder="Max"

id="nameInput"

onChange={setName}

/>

</div>

<div>

<label for="breedInput">Breed</label>

<select className="u-full-width" id="breedInput" onChange={setBreed}>

<option value="Labrador">Labrador</option>

<option value="Bulldog">Bulldog</option>

<option value="Poodle">Poodle</option>

</select>

</div>

<div>

<label for="ageInput">Age</label>

<select

className="u-full-width"

id="ageInput"

onChange={setAge}

>

{

[...Array(10).keys()].map(i => <option value={i}>{i}</option>)

}

</select>

</div>

</div>

<input className="button-primary" type="submit" value="Mint" />

</form>

</div>

);

};

const style = {

padding: '5rem',

background: 'white',

maxWidth: 350,

};

export default Form;

The FileSelector.js component we imported does not yet exist. So, next to Form.js, create another component named FileSelector.js to handle the image upload logic.

// components/FileSelector.js

import { useState } from 'react';

// We are passing `pet` and `setPet` as props to `FileSelector` so we can

// set the file we selected to the pet state on the `Form` outer scope

// and keep this component stateless.

const FileSelector = ({pet, setPet}) => {

// Read the FileList from the file input component, then

// set the first File object to the pet state.

const readFiles = (event) => {

const files = event.target.files;

if (files.length > 0) {

setPet({...pet, file: files[0]});

}

};

return (

<div className="">

<label for="fileInput">Image</label>

{/* Add readFiles as the onChange handler. */}

<input type="file" onChange={readFiles} />

</div>

);

};

export default FileSelector;

If you import Form.js component into App.js and insert it anywhere inside the main App container, you should see your form that looks similar to the one you see below:

# Minting logic

Here comes the interesting part. We will hook up the Mint button to actually mint a token based on user's input!

Switching gears here, let's head over to /src/flow/transaction and create a new JavaScript file named MintToken.tx.js. This module will send the Cadence transaction MintToken.cdc similarly to how we have used Flow CLI to do so previously.

Here I create a JavaScript module that interacts with each Cadence transaction or script and name it to reflect the Cadence code, appended by .tx.js or a transaction or .sc.js for a script. This is not a requirement and you're free to name them however you want.

Since there will be quite a lot going on, we will go slowly on this one. We will create a mintToken function that takes a pet object and does the following:

- Upload to NFT.storage. This uploads the metadata and image asset to NFT.storage, and retrieves the returned metadata that includes the CID (opens new window) of the data.

- Send a minting transaction with the metadata to Flow (in this case, the name, age, breed, and the CID of the data stored on IPFS).

- Return the Flow transaction ID if successful.

First, let's sketch up some placeholder functions to outline the steps:

// MintToken.tx.js

async function mintToken(pet) {

let metadata = await uploadToStorage(pet);

let txId = await mintPet(metadata);

return txId;

}

// We will fill in these functions next

async function uploadToStorage(pet) {

return {};

}

async function mintPet(metadata) {

return '';

}

💡 Where to catch an error?

Asynchronous functions which return aPromiseare fallable. Conventionally, you should prepare for the worst by catching the error. But the question is where to do this? The general rule here is if a function does not know what to do with the error, don't catch it. Delegate this responsibility to the caller who will hopefully know what to do. In the previousmintTokenfunction, we didn't handle the error because we wanted the calling function to handle it. This way, you are not making things worse by complicating the code with unnecessarytry-catchblocks that only obscure the errors. Let the one who knows better deals with it.

Next, fill in the body of uploadToStorage function. You will need your API key from NFT.Storage:

// Import required modules from nft.storage

import { NFTStorage, File } from 'nft.storage';

const API_KEY = "DROP_YOUR_API_KEY_HERE";

// Initialize the NFTStorage client

const storage = new NFTStorage({ token: API_KEY });

async function uploadToStorage(pet) {

// Call `store(...)` on the NFTStorage client with an object

// containing all of pet's attributes, and required image and

// description attributes.

let metadata = await storage.store({

...pet,

image: pet.image && new File([pet.image], `${pet.name}.jpg`, { type: 'image/jpg' }),

description: `${pet.name}'s metadata`,

});

// If all goes well, return the metadata.

return metadata;

}

# 1. Upload to NFT.Storage

NFTStorage.store(...) takes an object with arbitrary attributes and two required attributes, image and description. (Contrary to its name, the image attribute does not require an image file. It takes a File object which can contain any type of asset.)

The description attribute can be any arbitrary text up to $MAXLENGTH.

Then, we return the metadata returned from the call to the caller.

# 2. Send a minting transaction

Once we have the metadata from uploading to NFT.storage, we will have to send a transaction to mint the token on Flow with the metadata. Let's fill in the mintPet function.

import * as fcl from '@onflow/fcl';

import * as t from '@onflow/types';

import cdc from './MintToken.cdc';

async function mintPet(metadata) {

// Convert the metadata into a {String: String} type. See below.

const dict = toCadenceDict(metadata);

// Build a list of arguments

const payload = fcl.args([

fcl.arg(

dict,

t.Dictionary({ key: t.String, value: t.String }),

)

]);

// Fetch the Cadence raw code.

const code = await (await fetch(cdc)).text();

// Send the transaction!

// Note the `userAuthz` function we have not implemented.

const encoded = await fcl.send([

fcl.transaction(code),

fcl.payer(fcl.authz),

fcl.proposer(fcl.authz),

fcl.authorizations([fcl.authz]),

fcl.limit(999),

payload,

]);

// Call `fcl.decode` to get the transaction ID.

let txId = await fcl.decode(encoded);

// This waits for the transaction to be sealed, which is a recommended way.

await fcl.tx(txId).onceSealed();

// Return the transaction ID

return txId;

}

// Helper function to convert `pet` object to a {String: String} type.

function toCadenceDict(pet) {

// Copy the pet object so we don't mutate the original.

let newPet = {...pet};

// Delete the `image` attribute that contains a `File` object.

delete newPet.image;

// Return an array of [{key: string, value: string}].

return Object.keys(newPet).map((k) => ({key: k, value: pet[k]}));

}

As you can see, our mintPet function is a little involved.

The first step we took was to convert the pet data to a type our Cadence contract understands, which a dictionary of type {String: String}. Basically, if the object looks like this:

{

name: "Max",

age: 3,

breed: "Bulldog",

// ...

}

We then have to convert it to an array of {key: string, value: string} in JavaScript:

[

{key: "name", value: "Max"},

{key: "age", value: "3"},

{key: "breed", value: "Bulldog"},

]

This was what toCadenceDict function did, plus deleting the image attribute from the pet object because we didn't need it for minting on Flow.

After properly converting the object, we had to build a "payload" by calling fcl.args and pass an array of arguments. In this case, the metadata of type [{key: string, value: string}]. To facilitate this, we used types from fcl.types library.

Next, we fetch the corresponding MintToken.cdc raw code. This is a standard way of fetching raw text from another module.

Now comes the meaty part of this function: Sending a transaction.

const encoded = await fcl.send([

fcl.transaction(code),

fcl.payer(fcl.authz),

fcl.proposer(fcl.authz),

fcl.authorizations([fcl.authz]),

fcl.limit(999),

payload,

]);

There are a few ways to send a transaction, but fcl.send([...]) is the most explicit way.

We pass the Cadence code to fcl.transaction, and any integer from 0 - 999 to fcl.limit for the gas fee limit we are happy with. The payload is the metadata we converted previously.

The payer, proposer, and authorizations accept a function known as authorization function that decides the account (and effectively the keys) used to authorize the transaction. (If you're interested in deep-diving, check out Authorization Function (opens new window)). Here, fcl provided an authz default authorization function to makes signing with the emulator account easier.

# 3. Return the Flow transaction ID

Now all that is left to do is to return to the main mintToken function to complete it:

// This is a fallible function.

async function mintToken(pet) {

// The metadata contains the attribute `url` which is an IFPS URL

// pointing to the data.json.

const { url } = await uploadToStorage(pet);

// We want to include the IPFS URL to the blockchain, so we can

// "unpack" the token data when we query it later. So we create

// a new object with all of the pet's attributes plus `url`.

const txId = await mintPet({ ...pet, url });

return txId;

}

// Don't forget to export the function.

export default mintToken;

Our mintToken function is ready to work. We should return to Form.js, add a handleSubmit handler (right after setAge function), and pass to the onSubmit prop on the <form> element.

// Form.js

// On the top most of the module

import mintToken from '../flow/transaction/MintToken.tx';

const Form = () => {

// ... setAge function ...

const handleSubmit = async (event) => {

event.preventDefault();

try {

await mintToken(pet);

} catch (err) {

console.error(err);

}

}

return (

<div style={style}>

<form onSubmit={handleSubmit}>

{/* ... other elements ... */}

</form>

</div>

);

This wraps up the minting step! Here is the [full code][source] for a handy reference. Now you can test the UI, select an image file, fill up the metadata on the form, and click the mint button.

Feel free to sit back and appreciate what you have achieved. Now is the time to fill up your coffee and take a well-deserved break before we move on to the last bit: querying a token.

# Querying the token

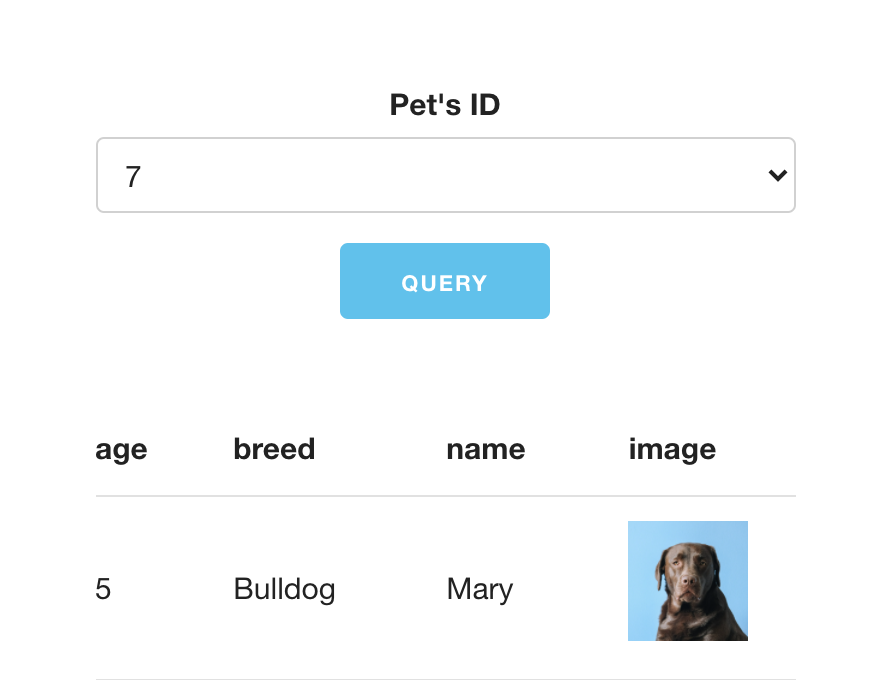

Now that we can mint pet tokens, let's build another form UI to query them for metadata and image.

This form should make a good use of the minting form. Once we're done, it will look similar to this:

I know Mary is obviously not a Bulldog, but you will get a chance to add your breed options later.

Let's start by creating QueryToken.jsx file inside the /components directory.

import { useState, useEffect } from 'react';

// QueryForm.jsx

const style = {

padding: '1rem',

paddingTop: '5rem',

background: 'white',

maxWidth: 350,

margin: 'auto',

};

const QueryForm = () => {

const [selectedId, setSelectedId] = useState(null);

const [metadata, setMetadata] = useState(null);

const [allTokenIds, setAllTokenIds] = useState([]);

useEffect(() => {

let getTokens = async () => {

// Set mock IDs for now

setTokenIds([1, 2, 3]);

};

getTokens();

}, []);

// Empty handler for now...

const handleSubmit = async (event) => {

event.preventDefault();

}

return (

<div style={style}>

<form onSubmit={handleSubmit}>

<div className="row">

<div className="">

<label htmlFor="idInput">Pet's ID</label>

<select

className="u-full-width"

type="number"

id="idInput"

onChange={(event) => setId(parseInt(event.target.value))}

>

{

// We want to display token IDs that are available.

allTokenIds.map(i => <option value={i}>{i}</option>)

}

</select>

</div>

</div>

<input className="button-primary" type="submit" value="Query" />

</form>

{

// We only display the table if there's metadata.

metadata ? <MetadataTable metadata={metadata} /> : null

}

</div>

);

};

const MetadataTable = ({ metadata }) => (

<table className="u-full-width">

<thead>

<tr>

{

Object.keys(metadata).map((field,i) => (

// Skip the `url` attribute in metadata for the table headings.

field === 'url' ? null : <th key={i}>{field}</th>

))

}

</tr>

</thead>

<tbody>

<tr>

{

Object.keys(metadata).map((field, i) => {

switch (field) {

// Skip displaying the url.

case 'url':

return null;

// Display the image as <img> tag.

case 'image':

return (

<td key={i}>

<img src={metadata[field]} width="60px" />

</td>

);

// Default is to display data as text.

default:

return <td key={i}>{metadata[field]}</td>;

}

})

}

</tr>

</tbody>

</table>

);

export default QueryForm;

As usual, we need to create JavaScript "bindings" to two Cadence scripts GetTokenMetadata.cdc and GetAllTokenIds.cdc. We will start with GetAllTokenIds.sc.js.

// GetAllTokenIds.sc.js

import * as fcl from '@onflow/fcl';

import raw from './GetAllTokenIds.cdc';

async function getAllTokenIds() {

// Fetch the `GetAllTokenIds.cdc` script as text.

let cdc = await(await fetch(raw)).text();

// Read the script, send it, and wait for the response.

const encoded = await fcl.send([fcl.script(cdc)]);

// Decode the response into a JavaScript array of IDs.

const tokenIds = await fcl.decode(encoded);

// Sort the IDs in ascending order and return the array.

return tokenIds.sort((a, b) => a - b);

}

export default getAllTokenIds;

Hopefully, by now you are an expert at this. It's worth switching back and taking a look at GetAllTokenIds.cdc to see how the Javascript bindings and Cadence scripts interact.

Next up, we create GetTokenMetadata.sc.js to execute the GetTokenMetadata.cdc script.

// GetTokenMetadata.sc.js

import * as fcl from '@onflow/fcl';

import * as t from '@onflow/types';

import raw from './GetTokenMetadata.cdc';

async function getTokenMetadata(id) {

let script = await(await fetch(raw)).text();

const encoded = await fcl.send([

fcl.script(script),

fcl.args([fcl.arg(id, t.UInt64)]),

]);

const data = await fcl.decode(encoded);

return data;

}

export default getTokenMetadata;

Again, you can review GetTokenMetadata.cdc to see the relationships between the interfaces offered and how we used them in this function.

Now we are ready to return to QueryForm.jsx. Import the functions we worked on:

// QueryForm.js

import { useState, useEffect } from 'react';

// Import these functions

import getAllTokenIds from '../flow/script/GetAllTokenIds.sc';

import getTokenMetadata from '../flow/script/GetTokenMetadata.sc';

import { toGatewayURL } from 'nft.storage';

const QueryForm = () => {

const [allTokenIds, setAllTokenIds] = useState([]);

const [selectedId, setSelectedId] = useState(null);

const [metadata, setMetadata] = useState(null);

useEffect(() => {

let getTokens = async () => {

// Instead of dummy token IDs, we call `getAllTokenIds`

// to get real IDs of all existing tokens.

const ids = await getAllTokenIds();

setTokenIds(ids);

};

getTokens();

}, []);

const handleSubmit = async (event) => {

event.preventDefault();

// Add this block to the submit handler.

try {

// Call the `getTokenMetadata` function and extract the

// IPFS URL from the data returned.

let metadata = await getTokenMetadata(selectedId);

let dataURL = toGatewayURL(metadata.url);

// Fetch the URL to get a JSON response, which contains

// an `image` attribute.

// create a new metadata object and set the metadata to the value.

let { image } = await (await fetch(dataURL)).json();

let newdata = { ...metadata, image: toGatewayURL(image) };

setMetadata(newdata);

} catch(err) {

window.alert('Token ID does not exist!');

}

}

// ...The component code unchanged...

}

In the useEffect callback, we replaced the stubbed ID array with the call to

getAllTokenIds function, which executed GetAllTokenIds.cdc and returned an

array of existing token IDs. We then call setTokenIds to set allTokenIds to

the array. This is used to fill up the <option> element with the IDs and act as

the UI guard to make sure users can only choose the available tokens to query.

In the "empty" handleSubmit handler function, which is called each time the query button

is clicked, we added a try-catch block which called getTokenMetadata with the ID user

selected in selectedId, and return the metadata of the selected NFT.

Remember that as part of metadata in minting, we included the url attribute from the

NFT.storage upload. This url is an IPFS URL in the form of ipfs://<CID>/data.json.

We are interested in this URL because it points to the JSON data containing the URL to

the pet image we uploaded to IPFS. To fetch it using JavaScript, we had to convert the IPFS

URL to the HTTP gateway URL with toGatewayURL (opens new window). Once we fetched the JSON and convert to an object, we access the

image attribute, convert it to HTTP URL, and include it along with other data in the new metadata

object we set the state with setMetadata. It is then ready for the MetadataTable component

to display.

Note that in the case of error, handleSubmit would call window.alert and display a simple popup

window to notify the user.

There was no change needed for the component code.

Now, try to mint an NFT with the mint form, and query it with the query form! Hopefully, it should all work as intended.

Congratulations! You have single-handedly built a NFT minting and querying marketplace on Flow. This has been a great achievement!

# Next steps

Flow's focus on developer's experience and the accessibility of its smart contract language Cadence, plus its low gas fee and high throughput, make it an extremely promising blockchain to build NFT-related apps on.

Because NFTs have assets that need to be stored off-chain permanently, using NFT.Storage to store them on the Filecoin network is a natural way to go as the first step to launch your NFT app on Flow quickly.

If you are still hungry to learn more about Flow and NFT.Storage, here is a non-exhaustive list of the resources to tackle next:

- Dive into the Cadence Language Reference (opens new window).

- Explore Flow Client Library (opens new window), especially the authorization.

- Familiarize with NFT.storage documentation (opens new window).

Last but not least, this tutorial is not perfect, and it can be improved with your help. Do not hesitate to create a pull request. No contribution is too small!